From some recent analysis of our data for the IAM/ktMINE Patent 1000, we noticed that banks are holding more patents these days. We decided to dive deeper into these holdings and to ask the following questions:

- What are the trends?

- Where did they come from?

- What might they do with them?

- Who might benefit or lose from the banks having all of these patents?

This is the first in a multi-part series where we have a look and see if the data could forecast any trends.

Of the financial institutions that we track, we take a deeper look at the following:

- The Bank of America

- The Bank of New York Mellon

- Deutsche Bank

- JP Morgan Chase

- Wells Fargo

- Wilmington Trust

These six banks collectively held nearly 80,000 U.S. grants in 2019, up an astounding 480% over the previous year. If the U.S. applications and foreign filings are included, the numbers are even more impressive.

Where did they come from?

Aside from applying for patents themselves, banks can acquire patents through business transactions such as mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Banks can also retain ownership of patents that are used as collateral for loans that default.

More on collateralized patents

Many companies will use patents as collateral in order to create liquidity on their balance sheets. On the plus side, this enables companies to pursue long term business strategies or address short term cash flow issues. On the downside, companies may be required to file an assignment with the USPTO as part of the condition of the loan and in doing so, they may relinquish their right to license or litigate for infringement.

The bank, for its part, can either realize any gains as the loan transaction concludes (loan fees, etc) or can reduce or diversify investment risk by securitizing the assets and trading them. In order to avoid conflicts or potential encumbrances, banks will seek to perfect their security interests in the assets by filing statements with the appropriate state (e.g. State Secretary of State, as part of the Uniform Commercial Code) or federal offices (e.g. U.S. Patent & Trademark Office). If the bank retains ownership of the patents, they can consider engaging in license or litigation activities themselves.

There are many articles reporting that 60-80% of the value of an enterprise is represented by intangible assets. The broad movement away from tangible assets extends back 30 or more years (see “2019 Intangible Assets Financial Statement Impact

Comparison Report”, Ponemon Institute LLC, April 2019). This observation, combined with improvements in analytics, intelligence, and information tools, may provide banks with the motivation and confidence they need to wade further into IP investments.

The Data

Transactions:

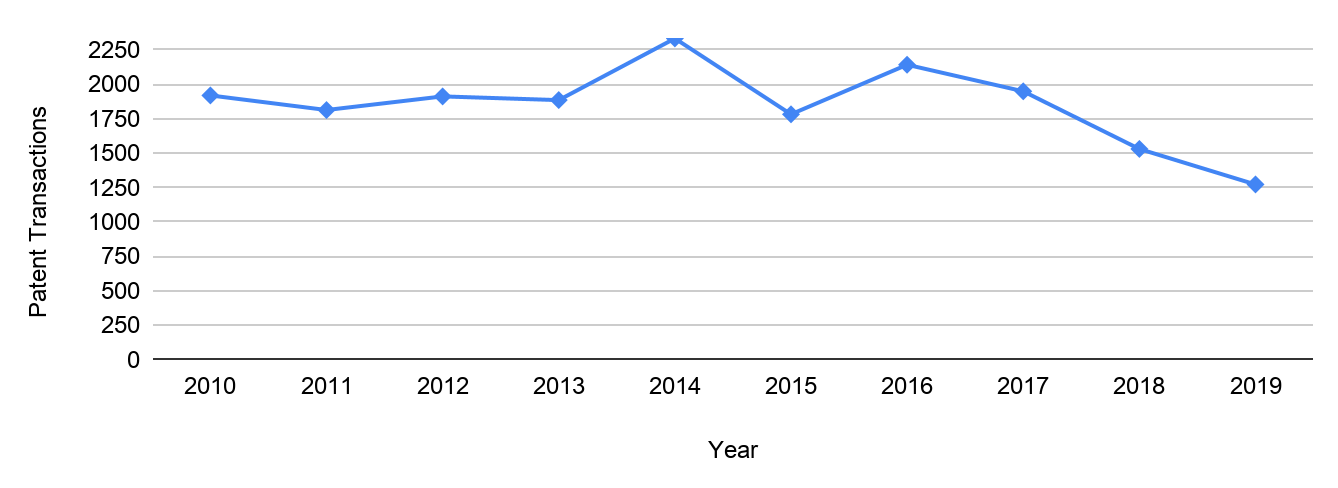

First, we noticed that during the past decade, the number of patent transactions by the top six financial institutions was steady near 2,000 and then dropped off slightly in 2018 and lower still in 2019.

Chart 1: Number of IP Transactions for listed Banks

Source: USPTO assignment data via ktMINE

This indicates that, at least for the top six, investment in IP transactions has been relatively consistent. The results don’t appear to align with any economic indicators (GDP, unemployment) or relevant legal decisions (Alice, etc…)

Assets per transaction:

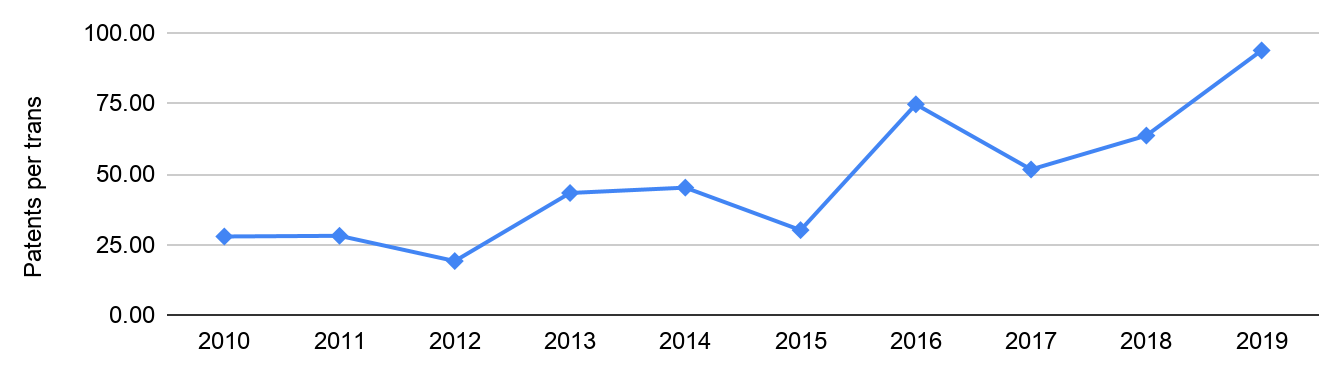

In contrast, we noticed that the number of assets per transaction has grown steadily during the same time period.

Chart 2: Patents per Transaction for listed Banks

Source: USPTO assignment data via ktMINE

This may be an indication that enterprises have grown more comfortable with the idea of leveraging their IP assets. Enterprises are able to articulate the value that their IP has with respect to their strategies. This information, taken with the previous chart, says that although there are fewer transactions, more patents are moving. As a counter observation, it is unclear if the mortgaging of IP represents a last-ditch effort to obtain access to cash. Is this a sign that more companies are in need of funding? Finally, it may also be an indication that banks, in search of additional venues of investment, have become more tolerant of such risk.

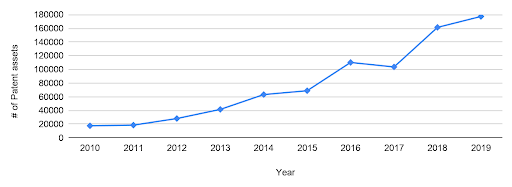

Running Accumulations:

Many of the transactions involved entities placing patent assets up as collateral, and once the loan is paid off, the expectation is that the assets would be reassigned from the bank, back to the original holder. The length of time that the assets are held by the bank depends on the terms of the agreement, but interestingly, during the past decade, the overall number of assets held by the banks has steadily increased:

Chart 3: Accumulation of Assets by listed Banks

Source: USPTO assignment data via ktMINE

It is possible that the terms of such agreements have lengthened in recent years, and many arrangements are still pending. It could also be that as part of the agreement, some of the patents do not return to the original holder and are ultimately retained by the bank.

Next time, we’ll have a look at other data, including bankruptcy and litigation activity, and talk about what options banks might explore in order to transact or monetize their patent holdings.