Supermac’s is Ireland’s largest fast-food restaurant group, serving an average of 320,000 customers per week. Pat McDonagh, the founder and CEO of Supermac’s, has been trying to expand his company into the rest of Europe since 2014. However, McDonald’s, the ubiquitous fast-food chain, has been in conflict with Supermac’s over trademark and branding issues for years. Are these small-fry intellectual property disputes, or is something bigger going on here? Is McDonald’s perhaps trying to block Supermac’s growth under the guise of brand protection?

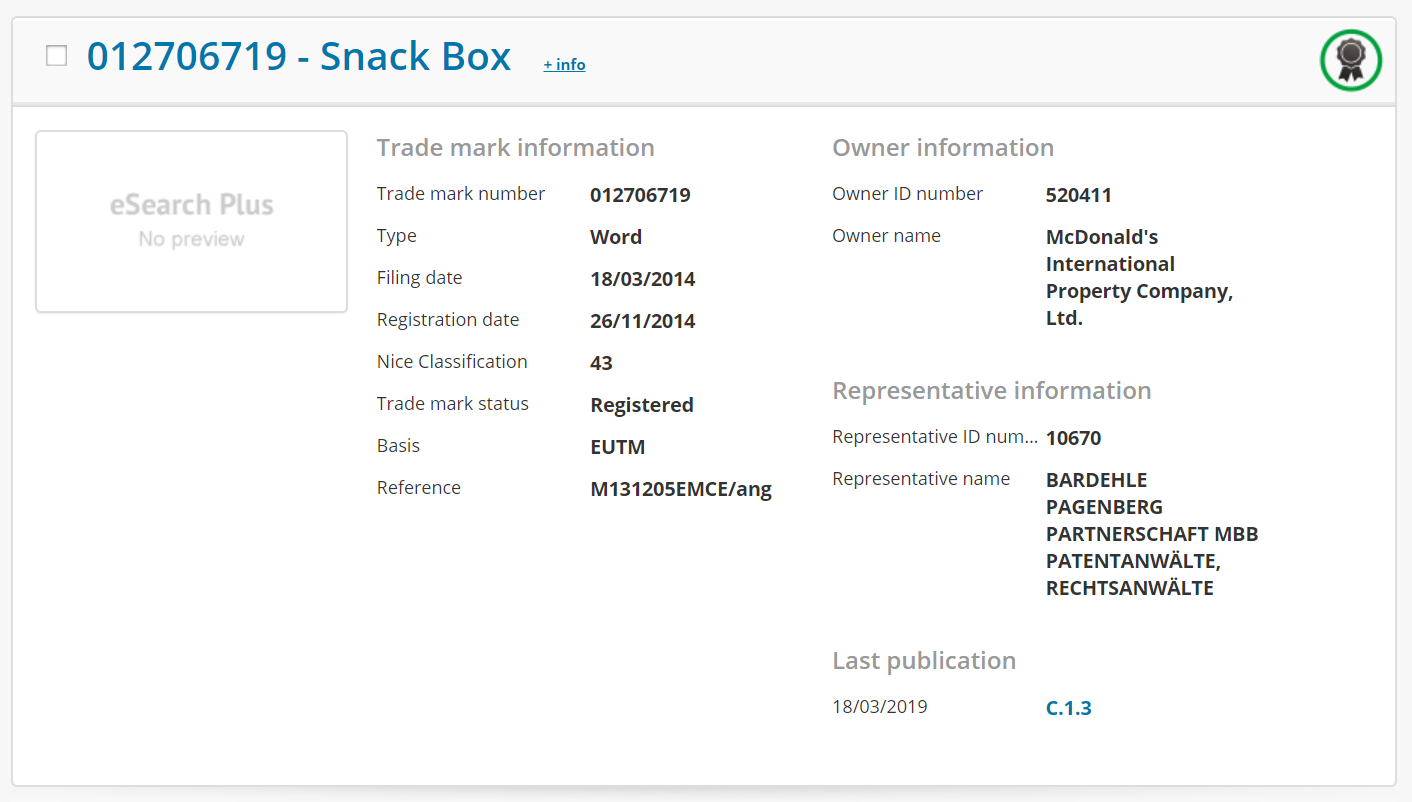

For years, Supermac’s has believed McDonald’s is deliberately attempting to prevent any potential competitors from succeeding and using disputes over intellectual property to disguise their true intentions. McDonagh has pointed to the fact that McDonald’s is the owner of a trademark on “Snack Box” as evidence of this.

Trademark data from the European Union Intellectual Property Office, or EUIPO, shows this mark as registered to McDonald’s:

But the Snack Box is one of Supermac’s most popular products — and is not offered on any McDonald’s menu.

Source: Supermac’s menu https://supermacs.ie/supermacs-food/

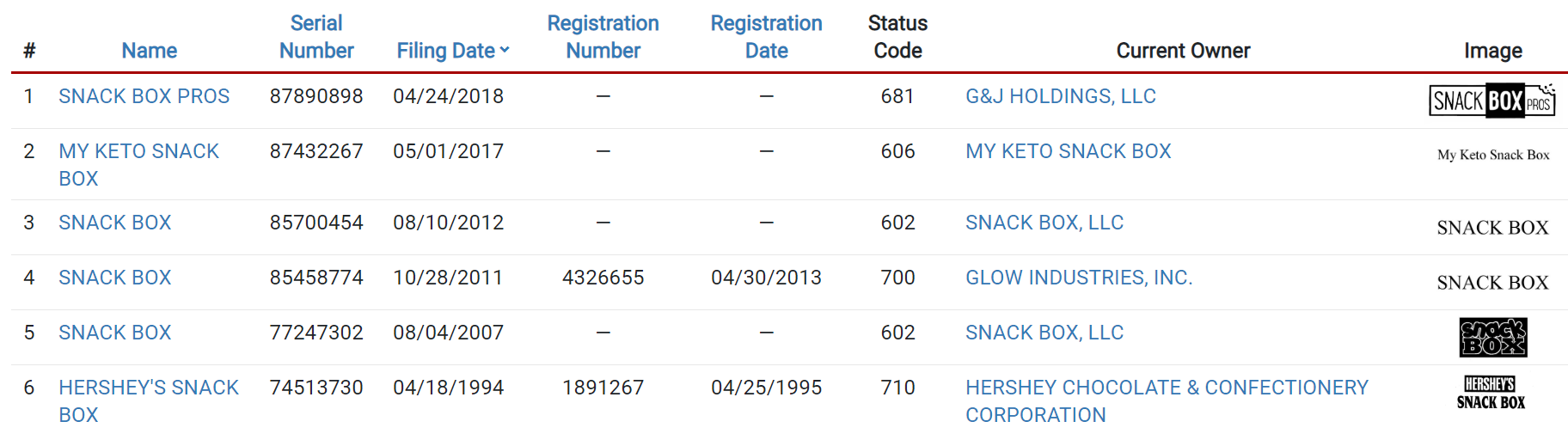

A search of ktMINE’s Trademarks database, which contains USPTO trademark data, shows no U.S. trademarks on “Snack Box” belonging to McDonald’s, suggesting that their concern for this particular mark is specific to the European region.

source: ktMINE Search App

Trademarks are meant to be held for products or services actually provided by a company. Collecting trademarks for the alternative purpose of preventing competitors from owning them is one example of controversial corporate behavior known as trademark bullying.

In 2016, Supermac’s brand applications (for a Europe-wide trademark) were opposed by McDonald’s in a complaint filed with the EU’s Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (OHIM, now known as the EUIPO). McDonald’s trademarks cover restaurant franchises in addition to actual burger products. McDonald’s claimed that customers would likely be confused by the two brands and their similarities, particularly the name “Supermac” with their number two bestselling product, the “Big Mac.” OHIM upheld most of McDonald’s claims, stating that there could be customer confusion over “whether Supermac’s is a new version of McDonald’s.” Without the trademarks necessary to sell its core food and drink products, Supermac’s halted its attempted expansion outside of Ireland and the UK.

In May 2017, Pat McDonagh called out McDonald’s trademark bullying in a complaint to the EUIPO. On the subject, McDonagh has stated,

“McDonald’s has literally registered the McWorld. It is trying to make sure that every word in the English language belongs to them if there is prefix Mc or Mac put in front of it. They have trademarked words like McKids, McFamily, McCountry, McWorld, McJob and McInternet in order to, over time, squeeze out smaller family-based businesses.”

According to ktMINE data, 50.6% of McDonald’s US trademark portfolio (filtered to exclude image-only trademarks and marks not currently “in use”) contains text with “Mc” or “Mac,” including the following:

- McGoblin

- McPunk’n

- McBunny

- McClass

- McHat

- McLots of Fun

- McMagination

(McWorld, McJob, and the rest of the examples quoted by McDonagh above were also found in ktMINE’s USPTO McDonald’s data.) While those outside of the company can only speculate as to McDonald’s true intentions with its Mc- or Mac-containing trademarks, they do form a significant proportion of its trademark portfolio.

A 2017 piece from the Washington Post on the Supermac’s/McDonald’s case lists several additional McDonald’s trademarks registered with the EUIPO. Some – like McBaguette (in France) and McPork (in Japan) – are or have been genuinely in use as the names of food and beverage items outside the United States, while the active (or historical) use of other marks is unclear.

In January of this year, the EUIPO ruled that McDonald’s had not proven genuine use of “Big Mac” as a burger or restaurant name in Europe, providing an opportunity for Supermac’s to trademark its brand beyond Ireland. Early this August, the EUIPO then ruled that McDonald’s had not proved genuine use of the “Mc” prefix on some of its products and services. (McDonald’s use of the “Mc” trademark was upheld on chicken nuggets and some sandwiches, however.)

On the EUIPO’s decision, McDonagh wrote to Reuters:

“This is a great victory for business in general and stops bigger companies from “trademark bullying” by not allowing them to hoard trademarks without using them.”

After McDonald’s lost their trademark rights, Burger King in Sweden took the opportunity to poke a little fun at the fast food giant:

Whether it involves accusations of trademark bullying or internet trolling, one thing is clear: when fast-food restaurants have beef with each other, consumers can expect inter-company conflict to manifest in very public ways.